“I started stealing at a very early age. I don’t know why: it wasn’t like I didn’t always have everything I wanted.”

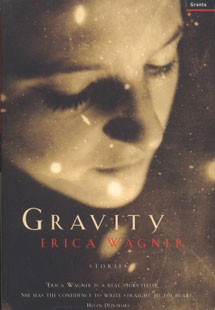

Gravity

In this assured and inventive debut collection, Erica Wagner’s haunting short stories range across space and time. From the solitary astronomer, whose desperation for another’s touch leads to destruction, to the Pharaoh’s daughter who sees her own death rising inexorably before her. From the small-town American, set free from normality by the disappearance of his wife and obsessed with raising a modern monument, to the young woman in the British Library whose seclusion is shattered by a simple note. From the priest turned lion-tamer, who finds that faith is essential in any vocation, to the young girl subverting her mother’s authority with the only weapon she possesses: her body.

Illuminating the loneliness of the human condition, the difficulty of making connections with others, and the fragility of those connections once made, these fresh and compelling pieces are the work of a true storyteller. Erica Wagner reaches into the fractured lives of her characters and finds moments of redemption, despair and exhilaration.

Reviews

Kate Hubbard, 8 November 1997, The Spectator

At first glance Gravity, Erica Wagner’s first collection of stories, exhibits a somewhat dizzying variety of subject and setting — Ancient Egypt, Thailand, the East Anglian fens, New York’s Upper East Side, the Reading Room of the British Library. And though all are described with authority and grace it is with a kind of relief that the reader seizes on recurring motifs — men who have no smell, mothers and daughters who disappoint each other, women who fall from great heights.

Falling, as it happens, is a key to Gravity, most aptly named and only in part for the absence of levity. Miss Wagner’s stories are interesting not for their diversity, but for their common ground: loneliness, or rather aloneness, and its concomitant “inexorable gravitational pull” towards another. Here are characters who find themselves alone, whether through choice, or abandonment, or bereavement, for whom life is a fragmented affair, a series of connections desired and feared, made and broken — territory, of course, which lends itself to the short story. The analogy between falling earthwards and falling into the embrace of another is made explicit in the title story, which is also one of the finest. ‘Gravity’ is a clever conceit on the laws of physics and desire, in which the solitary existence of an astronomer — who believes, erroneously, that ‘we are separated by distance and motion. All of us. All of us swing like planets, or comets, or stars, each on our own cosmic path’ — is disturbed by the arrival of a fellow astronomer, a young woman. Tragedy results.

This potential for destruction helps explain why Wagner’s characters so often seek to preserve autonomy, of which the holding of secrets is but a part. In ‘Please Don’t’, the oneness of a young woman researcher in the British Library seems impregnable, until mysterious notes begin to appear on her desk – “Please don’t sigh” etc. In ‘The Great Leonardo’ a priest abandons his vocation and turns to lion-taming, to “dancing with soft-furred death”, because of a woman who came to his church and gave “a shape to his fear”. At times connection is simply seen as a matter of a voice on a telephone, or a fleeting, but transforming touch. In ‘How Many There Are, How Fast They Go’ a woman viewing the body of her young husband, who has been killed in a car accident, is prevented from falling by the strong arm of a morgue attendant, leaving them “dancing, almost laughing, spinning on the low-lit floor to a faint canned tune in the distance”.

Occasionally Wagner’s stories seem to buckle beneath their own weight, much as the astronomer of ‘Gravity’ finds himself “collapsed inwards, contracted by a force invisible and all-pervasive”. Such is the case with “The Bends”, a slight tale about a woman who falls for an unsuitable thatcher before returning to her suitable PhD student boyfriend. And she betrays some of the anxiety of the first-time author to prove her versatility, her seriousness of intent. But the best of these stories are beautifully imagined and controlled — the chilly elegance of ‘Pyramid’, for example, where a Pharaoh’s daughter sacrifices herself to the construction of her father’s tomb, or ‘Mysteries of the Ancients’. Here a rare note of exuberance is sounded and another kind of monument appears, one affirming life rather than death, when a man consoles himself for the defection of his wife with a joyous, crazy project, a modern Stonehenge, built of used cars, in an empty lot. There is plenty here to make Wagner’s novel worth waiting for.

Frank Egerton, Literary Review, February 1998

The quality of Erica Wagner’s prose in her first collection of short stories is immediately obvious in the title piece, although the tone here is untypical of those that follow. The story makes a powerful opening statement about the themes that concern her. Its narrator, a forty-year-old American astronomer called Davenport, has withdrawn to a mountain-top observatory. In language that is measured and often redolent of the magical aspects of his discipline, he grows increasingly disturbing. He describes his sadistic and ultimately fatal sexual relationship with a visiting scientist, Dr Victoria Greenwood. Both characters are dissociated from normal responses as a result of their professional obsessiveness.

‘Stealing’ is set in Wagner’s native city of New York and is more indicative of the scale to which she works. It is the first of several poignant character studies exploring a range of domestic personal crises. Jeannie is a likeable, humorous woman trying to understand an episode in her childhood relationship with her mother. She tells us that her pilfering began as a reaction against her parents’ liberal attitude towards her. It became acute, she suspects, only when she realised that her mother thought of her as fat. He decision to take twenty-dollar bills in order to buy large quantities of food was perhaps a dislocated rebellion against the diet that her mother had put her on. “Because I was eleven, I couldn’t begin to hate her. I could only keep stealing.” Wagner develops the contradictions in Jeannie’s behaviour — her wish to be seen as compliant while also needing to defy — and the ambiguities inherent in the very act of remembering.

In this and other similarly successful stories — such as a woman’s ambivalent feelings towards her mother-in-law, and ‘Haircut’, in which a redundant Brooklyn-born executive pretends to his wife that he is still going out to work — much of the substance is in the realistic, and fascinating, backgrounds that are created for them. In ‘A Few Hours at Home’, it is the way Wagner is seemingly able to create suspense out of thin air that is astonishing. A schoolteacher who is on a camping trip in Wales telephones his wife: this is the first time they have been apart; she previously drifted from one unsatisfactory boyfriend to another before finding in him the security she craves; he is not the sort who would tolerate an affair. Later, her promiscuous past insinuates itself into her mind and the tension in this simple situation is stretched to breaking point. Her old address book, we are told, “hummed in her lap. She didn’t want anything to be different… But she saw that her happiness was a terrible, fragile thing, a blown glass globe with her inside.”

There are some stories which are less successful. ‘Please Don’t ’ is about a researcher working in the Round Reading Room at the British Library, whose life of quiet self-absorption is disrupted by a series of mysterious notes left on her desk. Although a witty and entertaining piece, the imbalance between the compelling plot and the relatively thin characterisation could leave us thinking: so what? Whether ‘Pyramid’ is clear enough in its own right, without reference to the Herodotus tale from which it is taken, is open to question.

Nevertheless, these quibbles are minor ones. Wagner’s great gift proves to be her ability to transform bleak situations through the careful geometry of her prose, which resonates with the redeeming mysteries of life.